Monday

Everyone knows the last major leaguer to hit .400 in a full season. It’s been the same answer for over 70 years. It’s Ted Willi…..

(Miming putting my hand to my ear to hear incoming information.)

What’s that?

(More miming, more info.)

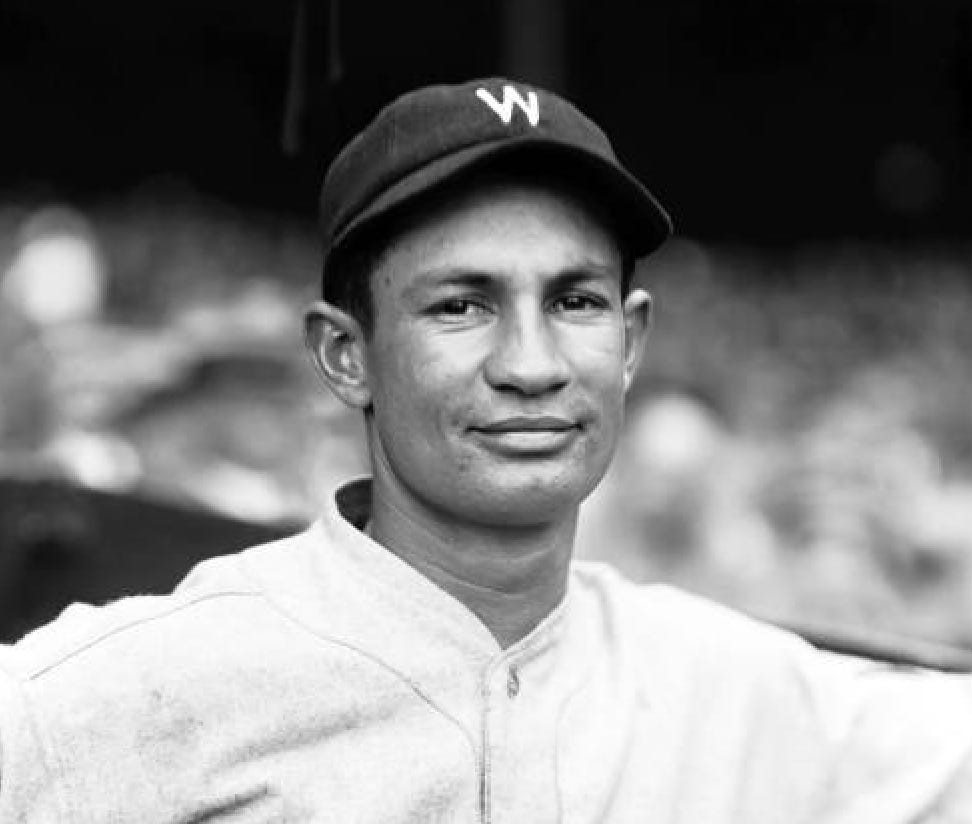

Ladies and gentlemen, we have a correction. The last major leaguer to hit .400 in a full season was not Ted Williams in 1941. It was actually two players in the Negro American League in 1948. One of the them was Hall of Famer Willard Brown, who hit .408 for the Kansas City Monarchs but didn’t even with the batting title. That honor went to Artie Wilson of the Birmingham Black Barons. He was born on this date in 1920, and batted .433 that year.

Wilson was a remarkably good player who is pretty much never mentioned now. In five seasons with Birmingham he batted .375/.436/.473 and was chosen to play in the East-West All-Star game seven times. He was a true slap hitter, averaging 250 hits per 162 games, none of which were home runs, though he ran well and hit enough gappers to have 30 doubles and 17 triples among those hits.

Signed by the Cleveland Indians for the 1949 season when he was still only 28, he was sent to the Pacific Coast League and hit .348 but didn’t get called up. The next year he hit .313 for the PCL’s Oakland Oaks, but still didn’t get called up. Traded to the Giants before the 1951 season, he made the team coming out of Spring Training but was almost never allowed to start a game. Instead he was mostly used as a pinch-hitter, struggled in the role, and was eventually demoted and then sent back to the PCL.

He never played in the major leagues again, though he continued to flourish on the West Coast with batting averages of .316, .332, .336, and .307 from 1952 to 1955. After slipping to .293 in an injury-plagued 1956 season, Wilson landed with the PCL’s Sacramento Solons in 1957, batted .264 in part-time work, and retired. A brief attempt at a comeback five years later didn’t end well (he hit just .186), and he hung up his spikes for good and worked at a Ford dealership for several decades, right up until his death in 2010 at the age of 89.

Sadly, Major League Baseball didn’t acknowledge that the Negro Leagues should be recognized as major leagues until a decade after Wilson’s death, so he never knew that he was officially the last big leaguer to win a batting title with an average over .400.

Tuesday

Tuesday was the 49th anniversary of Fred Lynn winning the Rookie of the Year Award in 1975. A few days later he became the first player to win both the Rookie of the Year Award and the MVP in the same season. I’m not completely sure he deserved the MVP that year, as there were quite a few contenders (Jim Palmer, Catfish Hunter, Rod Carew, John Mayberry, etc.) for the title of best player in the league, but he certainly wasn’t a bad choice.

It made me wonder, was there a prior Rookie of the Year who should have also been MVP? Here are the top contenders:

Dick Allen, 1964. Was third in the league with 8.8 WAR, led the league in runs while batting .318/.382/.557. Considering he was playing out of position but held his own at third base anyway, he would have been a worthy choice. The winner probably should have been Willie Mays, but it went to Ken Boyer despite both Allen and Ron Santo probably being better third basemen in the National League that year.

Carlton Fisk, 1973. He finished fourth and didn’t receive any first-place votes, and that was probably right. He was fifth in WAR at 7.3 among players to receive votes. Dick Allen won it and deserved it unless you’re just convinced the massive number of innings pitched by Gaylord Perry or Wilbur Wood made them more worthy.

Tony Oliva, 1964. He, too, finished fourth as he won the batting title by hitting .323 and also led the league in hits and runs. Oliva totaled 6.8 WAR, fifth-best among voter-getters, well behind the 8.1 posted by actual MVP Brooks Robinson.

Frank Robinson, 1956. Despite leading the league with 122 runs, batting .290/.379/.558, and totaling 6.5 WAR, he finished just seventh in MVP voting. He really didn’t have a case for winning it as Mays, Henry Aaron, and Duke Snider all had higher WAR scores, but he might have had a case over the actual winner, Don Newcombe.

Tommie Agree, 1966. No, he shouldn’t have won considering this was Frank Robinson’s Triple Crown season. But Agee’s 6.4 WAR was tied with Oliva for third-best among players to receive votes. He was an excellent defender in center field, winning his only Gold Glove, while also stealing 44 bases and hitting 22 homers. He probably deserved better than the eighth place MVP finish he got.

Wednesday

Two very good but not all-time great players, Mickey Rivers and Joe Adcock, were both born on this date, 21 years apart. They present a wonderful illustration of the different ways players can help teams win.

If we looked at nothing by the side-by-side summary of their careers that we can get from Stathead, it sure looks like Adcock was better.

Not very close, is it? Adcock was pretty obviously the better hitter of the two. Better at slugging, better at getting on base, and better in the context of the home parks and leagues in which they each played. He even played longer, getting into nearly 500 more games. So case closed, right?

Well, no.

Baseball is more than just how well you swing the bat, and we finally have better tools to help us measure that. Once we account for those things the picture painted above starts to shift.

For instance, Rivers was a significantly better base runner than Adcock. We see that in their respective stolen base totals, which favor Rivers 267-20. As expected, Rivers not only stole more but also stole more successfully, 75% of his attempts compare to just 39% for Adcock. Combine that with his superior ability to take extra bases (55% of the time compared to a 45% league average and just 32% for Adcock), and Rivers was worth +39 base running runs during his career while Adcock was at -23. A 62-run swing closes a lot of ground between the 160-run gap Adcock enjoyed just from batting.

Because he was a faster player, Rivers also hit into a significantly smaller number of double plays. Adcock grounded into 223 during his career, well above the league average, resulting in -27 runs from double plays. Rivers, on the other hand, only grounded into 44 double plays in his entire career, well below league average. That was good for +29 runs from double plays, representing a 56-run swing in Rivers’ favor.

Then there’s defense. Adcock was a pretty average first baseman, worth +2 fielding runs during his career. Rivers was also a pretty average defender, worth the same +2 fielding runs as Adcock. The difference, of course, is that Rivers produced those +2 runs from center field which requires much more skill than it does to play a decent first base. Once that difficulty is accounted for, Adock’s defense is debited by 90 runs while Rivers’ is only debited by 14 runs, almost all of that from his final two seasons in which he was mostly a designated hitter.

Add all of that up and the positions of the two players are flipped.

Adcock: 217 batting runs + (-23) base running runs + (-27) double play runs + 2 fielding runs + (-90) positional adjustment = 79 runs above average.

Rivers: 57 batting runs + 39 base running runs + 29 double play runs + 2 fielding runs + (-14) positional adjustment = 113 runs above average.

All things considered, this math results in Adcock totaling 33.5 WAR in his career, while Rivers totaled 32.7 WAR. Since Rivers did that in far fewer games, he was probably the more valuable overall player on a game-by-game or year-by-year basis (3.6 WAR per 162 games compared to 2.8 for Adcock), but Adcock makes up for that by having greater longevity.

I’m not smart enough to know if all the math for these various measures is done right, and some of it, like the degree of the positional adjustments, I flat-out disagree with, but I do know that all of it basically tracks with common baseball sense. Sluggers who mash for 17 years as decent first basemen have solid value. Speedy center fielders who don’t slug as much and don’t play as long but are above average in pretty much every other aspect of the game also have solid value, just in an entirely different way. The fact that they come out to almost exactly the same career WAR totally tracks with everything I know about baseball, and it’s why I accept WAR as a valuable metric even if I don’t fully understand the math.

Thursday

Buddy Myer, the longtime second baseman for the Washington Nationals/Senators, died on this date in 1974, and while I don’t think he should be in the Hall of Fame, he was a really good player and his near-complete dismissal by Hall of Fame voters does beg the question about why some very similar players were elected.

First, let’s give Myer his due. Despite having virtually no power (38 career homers), he was a solid offensive contributor in a variety of ways. He won a batting title in 1935, hit over .300 nine times, and finished with a career average of .303. He also drew a lot of walks, including a career high 102 in 1934 and 965 for his career, totaling more than twice as many walks as strikeouts. He also ran pretty well with 157 career steals that included a league-leading 30 in 1928. Four times he got MVP votes including a 4th-place finish in 1935 when he not only batted .349 but drove in 100 runs despite hitting just 5 homers.

Defensively he was never great, but always pretty solid. They started him as a shortstop and he wasn’t very good there, but once he settled at second base he was typically average or just a touch better. In the ten years he was a full-time second baseman (1929 to 1938) he totaled +12 fielding runs and 5.1 defensive WAR. Coupled with his solid offense and base running, he was worth about 4.2 WAR per 162 games in those seasons.

It was a solid career, but not terribly worthy of the Hall of Fame. That was reflected in the voting when he was eligible. In 1949 a single writer voted for him. He never got any other votes and hasn’t been on any final Veterans or Eras Committee ballot ever since. There is no loud group of baseball nerds clamoring for his entry into Cooperstown.

But then, how did these guys get elected?

I mean, okay, Evers and Fox had MVP awards, and Evers and Schoendienst had World Series titles, and Fox won Gold Gloves (which didn’t exist during Myer’s career), but is there really much to distinguish them from Myer? He was probably the best hitter of the group, both in raw numbers and in the context of the time he played, and there’s no evidence that his defense or base running were liabilities that should drag down his overall reputation.

Again, I’m not saying he should be in the Hall of Fame. He’s the 32nd-ranked second baseman in history using the JAWS system, and there are plenty of more worthy players at that position who deserve to be elected before him (Bobby Grich, Lou Whitaker, Willie Randolph, etc.).

But his omission does shine a light on these other guys who did manage to get elected. I’m not sure Fox (24th), McPhee (29th), Evers (31st), or Schoendienst (36th) do much to raise the standards of second basemen in the Hall of Fame. Myer fits neatly in this group. The real question is why the other members of that group have plaques in Cooperstown.

Friday

Finally, Friday marked what would have been Fernando Valenzuela’s 64th birthday, as well as the 46th anniversary of Ron Guidry winning the 1978 American League Cy Young Award. Since they were both lefty starting pitchers who had Cy Young seasons but otherwise short careers due to injury, and they played mostly for the two teams that just played in the World Series, let’s do a quick comparison between them.

Wow, there really isn’t much to separate them, is there? I mean, yeah, Guidry was probably the better pure pitcher of the two. He prevented runs better, struck out more, walked less, and so on. If we look at just their best 7-year stretches, though, the gap closes quite a bit. For the 1981-1987 years for Valenzuela and 1977-1983 years for Guidry, their 162-game averages were comparable.

Guidry: 19 wins, 2.96 ERA, 131 ERA+, 245 IP, 193 K’s, 3.05 FIP, 5.8 WAR

Valenzuela: 16 wins, 3.11 ERA, 115 ERA+, 260 IP, 210 K’s, 3.06 FIP, 4.5 WAR

Still Guidry, but not by as much. Since had added a great bounce-back season in 1985 (22-6, 3.27 ERA), while Valenzuela did not, I think most people would recognize that Guidry was the better pitcher. But then throw in the fact that Valenzuela could hit, too, and managed to contribute over 500 more innings, and was a cultural phenomenon on top of that, and it draws them pretty even in my mind.

It’s good their teams squared off again in the Fall Classic. It’s even better that Fernando’s old team took home another title while wearing his number on their sleeves.

This Week’s Editions

Monday: Baseball Remembers: Sam Jethroe

Tuesday: Twin Peaks: Wally Berger vs Earl Averill

Wednesday: Educating Twitter, Mike Trout Edition

Thursday: Decisions, Decisions: Snubbing Biz Mackey

Great stuff. I assume that Fox got in because of the MVP, as you said, but also because he made the All-Star team in 12 different seasons, got MVP votes in 10 seasons and led the league in hits 4 times plus was second 4 times (in part because he regularly led the league in games played, at bats and plate appearances). Plus, he only stopped playing in the mid-60s, so he was familiar to the voters. Schoendienst also made a lot of All-Star teams (10), received MVP votes in 10 different seasons and stopped playing in the early '60s. And he led the NL in fielding percentage six times, something the voters likely cared about back then. Plus, he held the record for consecutive chances without an error until it was broken by Ryne Sandberg in 1986. And although he was elected as a player, it probably did not hurt his chances that he managed the Cardinals to two pennants and one World Series. Myer, on the other hand, was only an All-Star twice -- of course, in part, because there was no All-Star game until 1933, his 8th season in the majors -- and received MVP votes 4 times. Plus, Myer was not immortalized in a poem (unlike, of course, Evers). I am in no way saying that Fox and Schoendienst were in any way more deserving of induction than Myer but I think this explains the likely reasons why they -- at least Fox and Schoendienst -- were inducted and Myer was not.

Hey Paul - You got me again with Buddy Myer who I barely knew if at all. Great point that the other HOF 2B on the list had little on Buddy. The Joe Adcock - Mickey Rivers thing I am not as with the idea that 'Mick the Quick' was an equal. Mainly because Adcock was a feared hitter in the Braves' lineup and I don't think any team ever had fear when it came to pitching to Rivers. The impact of a tough hitter in the line up is a hard thing to quantify I realize. But an interesting comparison!