It’s been over two years since I wrote an edition about Nomar Garciaparra. It started as a discussion of his odd habits in the batters box, as his name had come up in relation to the (then) new pitch clock rules. Folks who remembered his rituals assumed he’d have been in violation of the new timer rules a lot, but I think that probably wasn’t the case, as you’ll see.

From there I shifted into the real discussion, which was about how good a player he was in his prime. Because of how the second half of his career went, as well as the unfortunate timing of the Red Sox becoming good and breaking their 86-year curse only after Garciaparra was traded away, his early years are sometimes lost in the noise that followed.

That’s unfortunate because before he got hurt Nomar was a force of nature, a profoundly impactful shortstop who was easily on his way to the Hall of Fame if he’d managed even a semi-normal decline phase to his career. That didn’t happen, of course, so the Hall didn’t come knocking for him.

But maybe they should anyway.

Here’s that piece from March, 2023, updated and edited a bit, and unlocked for everyone.

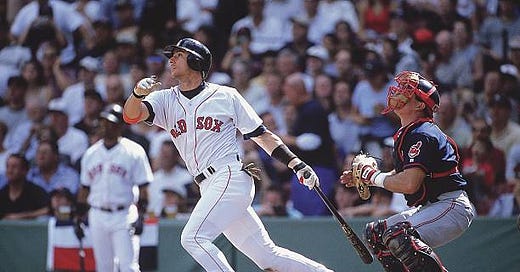

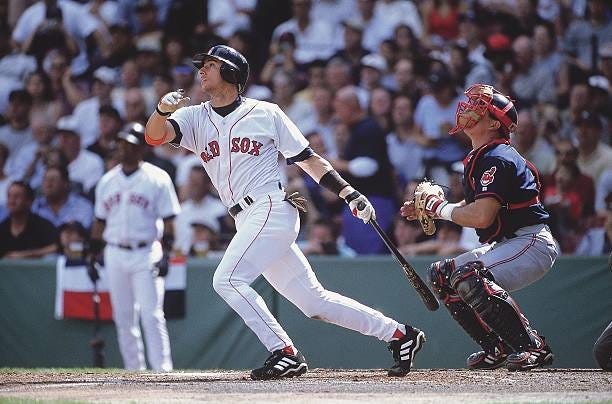

As the discussion of baseball’s new pitch clock continues during Spring Training, it was probably inevitable that Nomar Garciaparra’s ritual before every pitch would eventually be mentioned. For those who don’t remember it, here’s a refresher:

It really was glorious to behold.

I understand that all that movement and apparent delay is an easy target for people who want to make the point that the new clock rules will impact some hitters’ rituals. That said, this seems to be a poor example.

Yes, Nomar had a lot of little tics and adjustments, but he actually accomplished them in a pretty short amount of time. From the point he starts his glove and wristband adjustments to the point he finishes and has both feet in the batter’s box and his head facing the pitcher, maybe 4 or 5 seconds has elapsed. That puts him at 10 or 11 seconds left on the pitch clock, in full compliance with the new rules that force him to be ready with 8 seconds left.

All of those toe taps and bat twirls happen with both feet in the box and him “alert” to the pitcher, which is perfectly legal under the new rules. Sure, a pitcher might force him to shorten some of that if they start their motion as soon as he’s in the box, but it doesn’t seem he’d have to modify very much of it. His routine compressed a lot of motion into only a few seconds.

Still, Nomar’s routine being invoked has given folks a chance to recall his career, and ask an old question again:

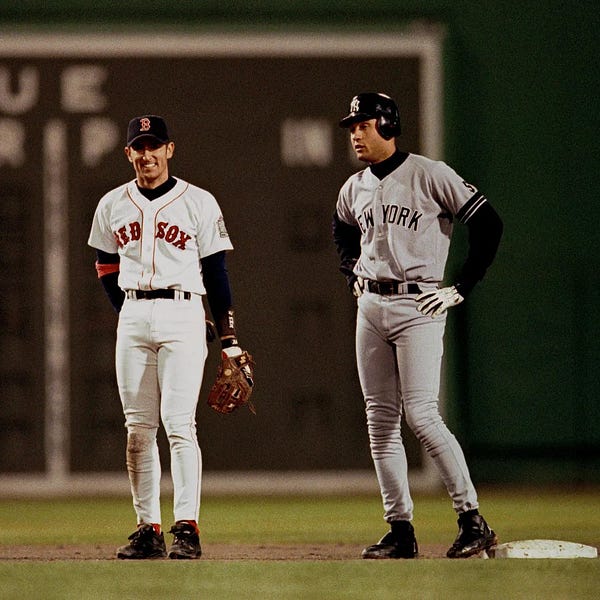

The key to that question, of course, is “prime.” Derek Jeter quite clearly had the better career. He’s in the Hall of Fame, and should be. He’s one of the best 4 or 5 shortstops in the history of the sport.

But Nomar had a better prime.

I mean, sorry, but it’s just true. Nomar’s prime was 1997 through 2003, and then injuries completely derailed his career. Even one of his prime seasons, 2001, was almost completely washed out by an injury to his wrist. But, when he was healthy, he was simply a better player than Jeter, especially if we define “prime” as the best seven years of his career, as Jay Jaffe does in his JAWS calculations*, because that would have been the same 1997-2003 timeframe for Jeter. Unlike Nomar, Jeter had other good individual seasons outside of that period, but no 7-year stretch that was better.

(*Note: Jaffe uses the best seven years even if they weren’t consecutive, so the WAR7 totals in his calculation are different. Even so, it still slightly favors Nomar over Jeter, 43.1 to 42.4. Nomar’s WAR7 total is 13th all-time among shortstops, and almost exactly matches the 43.2 average of all Hall of Fame shortstops.)

Don’t take my word for it. Here are their stats for those years:

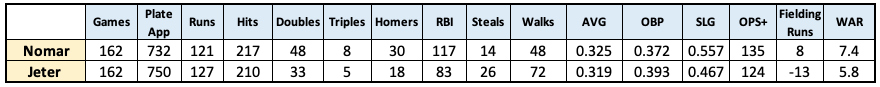

On a per-162 game basis, it looks even worse for Jeter:

Mostly those are offensive numbers, but notice the Fielding Runs as well. There’s an argument to be made that they were close enough offensively to call it a wash, but defensively they were night and day. Jeter posted a horrific -82 Fielding Runs during these years, while Nomar was at +43. Jeter’s range factor during these years started at 4.41 per game and dropped gradually to 3.64 by the end of this period. It was below the league average every single year. Nomar’s, on the other hand, started at 4.57 and barely moved. By 2003, it was still at 4.31, and he was over or around the league average every year.

When the offensive gap between them is added to the defensive gap, Nomar posted 41.1 WAR during this time while Jeter posted just 37.5, despite Nomar playing 136 fewer games due to that 2001 injury. On a per-162 game basis, Nomar’s WAR during these years was 7.4 to Jeter’s 5.8, a gap of over 25%.

Their peers, the fans, and the writers all recognized that Nomar was a bit better. Both players made 5 All-Star teams during these years, but only because Garciaparra was inexplicably left off the 1998 team despite having a year that saw him finish second in the league in MVP voting. Speaking of which, their respective finishes in MVP voting during Nomar’s six healthy seasons of this span reveal a lot about how they were viewed in baseball:

1997 - Nomar, 8th; Jeter, 24th

1998 - Nomar, 2nd; Jeter, 3rd

1999 - Jeter, 6th; Nomar, 7th

2000 - Nomar, 9th; Jeter, 10th

2002 - Nomar, 11th; Jeter, no votes

2003 - Nomar, 7th; Jeter, 21st

So which of them had a better prime is pretty easy to answer. It was Nomar, no question. The more interesting question, in my view, is whether Nomar’s prime should be enough to warrant election to the Hall of Fame.

The voters of the BBWAA looked at that question and resoundingly answered “No.” He appeared on the ballot for the first time in 2015, and got just 30 votes. The next year his total dropped to 8, and his time on the ballot came to an inglorious end.

I’m not sure it should have. Players have been elected with lesser résumés than Nomar’s, and with a peak nearly as short. For instance, here are the career stats of four shortstops, Nomar and three Hall of Famers. Tell me which one doesn’t belong.

Now, I’m not saying that Nomar should be elected because he’s got a similar or better case than these three, but I am saying he’s definitely got a case, one that is better than a few guys at his own position who managed to get elected.

Short career peaks have not barred players from being elected in the past, even if the peak is as short as six or seven seasons. The most obvious example is Sandy Koufax, but you don’t need to look at anyone who was that dominant during their peak. In fact, you don’t have to go back any further than 2022 to find a guy who was elected to the Hall of Fame on the strength of a high-peak career that was cut short by chronic injuries. Here’s Nomar’s average 162-game peak season compared to Tony Oliva’s:

Oliva has the advantage of having eight seasons in his peak instead of seven, but it otherwise seems pretty comparable to me. Throw in the fact that Nomar accomplished this as a shortstop and you get a gap in their WAR totals on a 162-game basis of 7.4 for Nomar to 5.8 for Oliva, the same gap that divided Nomar’s prime from Jeter.

Again, I’m not necessarily saying that Nomar belongs in the Hall of Fame. There are far more egregious examples of guys who have been overlooked unfairly. But, just like Phil Rizzuto, Hughie Jennings, Travis Jackson, and Tony Oliva all got a second look by the various iterations of the Veteran’s Committee, and eventually found themselves in the Hall of Fame 30, or 40, or 50 years after their careers ended, Nomar’s career deserves a similar second look.

His exceptional peak is worth being remembered for far more than his quirky rituals before each at-bat.

Saw him at Georgia Tech. Tremendous start. Think he was a roider though. Met him once and he was quite nice. Mentioned I’d seen him in college. Varitek was on the same team. Imagine!