*This was originally posted in April, 2023. I’ve edited it a bit, but otherwise it’s unchanged.

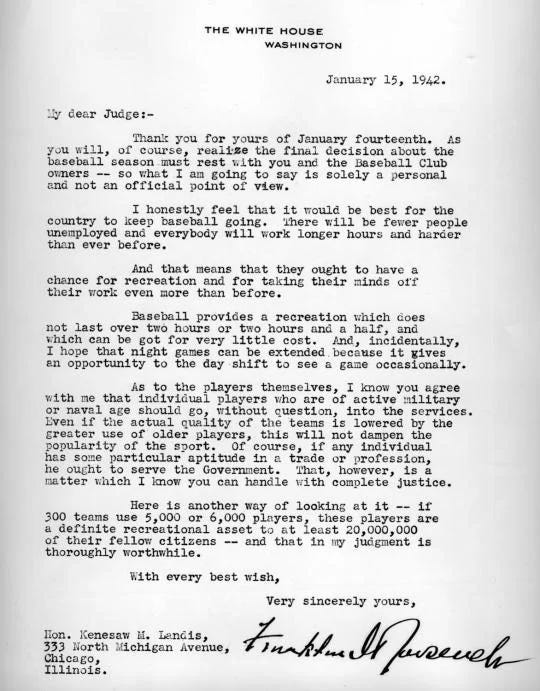

About a month after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, the commissioner of baseball, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, sent a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt. The time to report to Spring Training was approaching, and with the armed forces having the first priority for able-bodied young men, Landis was seeking guidance from Roosevelt on what organized baseball should do.

“…[I]nasmuch as these are not ordinary times, I venture to ask what you have in mind as to whether professional baseball should continue to operate.”

Roosevelt was quick to respond, sending Landis his full thoughts on the matter the next day. He was very clear; baseball should keep playing during the war.

Roosevelt’s letter became known as “The Green Light Letter”, giving baseball the go-ahead to keep playing. The rest, of course, is history. While most of the major league-quality players ultimately missed playing time while serving in the military or working a critical war-related job, the major leagues, and many minor leagues, played on.

A couple of thoughts about that famous letter jump out.

First, it seems absurd in retrospect that the statistics from the 1943-1945 seasons - the seasons when most of the real big leaguers didn’t play at all - are still considered “major league” and are included in the official record books. It’s clear that most of the players only had roster spots or got regular playing time because their competition was gone. A few examples:

Lou Klein, who was a .250 hitter in Double A in 1942, found himself hitting .287/.342/.410 as the Cardinals’ regular second baseman in 1943, and had the third-most WAR in the National League. After a year of military service in 1944, Klein returned in 1945 and never again played even 60 games or got more than 158 plate appearances in parts of four other big league seasons.

From 1939 to 1942, Eric Tipton was a journeyman outfielder who played for three organizations, never got more than 207 big league plate appearances in a season, and had a career major league OPS+ of 85. Then he found himself installed as the Reds’ regular left fielder for the three years during the war when most of the real big leaguers were gone, and had a 119 OPS+ in those years. He never played in another big league game after the war ended.

Nels Potter was a bad pitcher for Cardinals, Athletics and Red Sox from 1936 to 1941 (22-39, 5.81 ERA) and was out of baseball in 1942. He signed with the Browns before the 1943 season, and suddenly was one of the better pitchers in the American League (44-23, 2.68 ERA, 9th in MVP voting in 1944), a level he couldn’t come close to sustaining once the war ended.

A guy named Mickey Rocco* bounced around the minor leagues for eight seasons beginning in 1935, without ever sniffing the big leagues. Suddenly, at the age of 27 in 1943, he found himself the starting first baseman for the Indians, a position he’d keep for three seasons. He led the American League in games and at-bats in 1944, and had a 107 OPS+ for those three years. Once the war ended, Rocco lost his job and played just 34 more big league games.

(*Note: And if you’re my age, simply reading his name probably conjured up images of Burgess Meredith from “Rocky”.)

Ed Heusser posted a 4.44 ERA in parts of four big league seasons from 1935 to 1940, and didn’t pitch in the big leagues in either 1941 or 1942, but, as a 35-year old replacement for the Reds, he led the National League with a 2.38 ERA in 1944.

In 1944-45, Snuffy Stirnweiss batted .314 with a 142 OPS+, led the American League in runs, hits, triples and stolen bases both years, won a batting title, and finished 4th and 3rd in the MVP voting. Once the real major leaguers returned, Stirnweiss batted a combined .247, with an OPS+ of 83, and was done as a regular player before he turned 30.

Solid major leaguers got enormous boosts to their normal production during the war. From 1934 to 1942, Phil Cavarretta was an average major league hitter. (.274 average, 101 OPS+), and after the war, from 1946 to 1955, he was a bit better (.294 average, 119 OPS+) but struggled to get regular playing time. In between, from 1943 to 1945, Cavarretta was one of the finest players in the National League, batting .322, with a 145 OPS+, and winning a batting title and an MVP award.

And the Reds called up 15-year old Joe Nuxhall, and the Browns gave over 250 plate appearances to one-armed Pete Gray, and so on, and so on. You get the idea, I’m not breaking any news here. Even FDR knew the quality of play was going to drop, he said so right there in the letter:

“As to the players themselves, I know you agree with me that the individual players who are active military or naval age should go, without question, into the services. Even if the actual quality to the teams is lowered by the greater use of older players, this will not dampen the popularity of the sport.”

What I’m wondering is why we should consider these to be major league seasons if they were played mostly by players who clearly weren’t of major league quality.

That’s the exact reason used by Major League Baseball to deny recognition to the accomplishments of many of the Negro League seasons, and all of the seasons played in Japan, or Mexico, or the Caribbean. It’s the reason why the records from the National Association, the first actual professional league, are often not recognized as “major league.” It’s the reason why Major League Baseball decided not to play at all during the player strikes of 1981 and 1994-95 rather than use replacement players.

But here we are, pretending that the Yankees, Cardinals and Tigers won actual “World Championships” during the war years, worthy of the same trophies and flags earned in other seasons. It just seems sort of inconsistent and silly to continue the charade after all these years.

My other thought about FDR’s letter was this quote:

“Baseball provides a recreation which does not last over two hours or two hours and a half, and which can be got for very little cost. And, incidentally, I hope that night games can be extended because it gives an opportunity to the day shift to see a game occasionally.”

Pretty savvy of Roosevelt to see the need for night baseball, though his thoughts about costs are obviously outdated now. But what strikes me even more is his comment about the length of games. Two or two-and-a-half hours was the norm back then, and the recent rule changes that include implementing a pitch clock are finally bringing us back toward that norm. Already we’ve seen a drastic reduction in game length compared to the years before those changes. We’re not back to the 2:00-2:30 range yet, but 2:39 in 2023 and 2:36 on 2024 is a pretty good start.

Maybe we’ll get back there someday. I’d bet on that before I’d bet on Major League Baseball taking those wartime World Series titles away.

Great read and interesting premise Paul. IMO keeping the game going during wartime despite the lower level of play, was a good enough reason to count those seasons as any other.

Your argument isn’t supported by *all* of the data, you merely cherry picked certain players to buttress your argument. I can do the same thing to argue the other way, that certain great players played about the same during and after the war, which demonstrates the quality hadn’t slipped that much: Hal Newhouser had 20.5 bWAR from 1943-45 and 22.0 bWAR from 1946-48. Stan Musial was still playing in 1943-1944 but his three best years in bWAR were post WWII. Vern Stephens’s production from 1943-45 was on par with his post WWII production from 1946-49.

You may have a point about MLB quality of play during 1943-45, but you’re going to have to do much more comprehensive data analysis to make a compelling argument that MLB should throw out those years.