Friday Stuff

(Note: Our break continues this week, so Friday Stuff this week is unlocked and uses entries from archived editions. We will be back with all new stuff on Monday, February 9.)

Monday

This would have been the late Red Schoendienst’s 103rd birthday*, and I think everyone needs something in their life that they love as much as Schoendienst loved the St. Louis Cardinals.

(Note: Well, I guess it’s his birthday regardless of his status, isn’t it?)

He grew up in Germantown, Illinois, which is now about a 45-minute drive from the heart of St. Louis. His dad was a coal miner, and the family didn’t have running water or electricity. After dropping out of school in the heart of the Great Depression to help his family, Schoendienst suffered an injury on the job that nearly cost him his left eye. After much discussion of removing it, the eye was finally saved, but he had trouble tracking some pitches from right-handers after that and decided to become a switch-hitter to solve the problem.

When the Cardinals held an open tryout in early 1942, the 19-year old Schoendienst impressed the club enough that they eventually offered him a contract in the Class-D Georgia-Florida League. He did well there, and moved up to the Double-A Rochester Red Wings the next season as their starting shortstop. World War II interrupted his career for a couple of years at that point, but he was back in time for Spring Training in 1945. The Cardinals liked him and wanted him on the club to start the season, but they already had Marty Marion at shortstop. Schoendienst was asked to switch to left field, a position he’d never played professionally, but he agreed to it.

He never spent another day in the minor leagues. Moved to second base for the 1946 season, Schoendienst settled in there for the next decade, and began his trend of doing pretty much anything the Cardinals organization needed him to do. Switch-hit? Sure. Move to the outfield? Fine. Move back to second base? No problem.

Even though the wasn’t a speed merchant at all, St. Louis wanted Schoendienst to run more when he was a rookie. He proceeded to lead the league in steals. At a time when the team was regularly in the bottom half of the league in scoring and needed more pop in the lineup, Schoendienst was dropped to the middle of the order and set a new career high in homers. Another year he led the league in sacrifices. His willingness to do whatever they needed was one of the constants of his game, along with durability and sound defense.

His glove was always there, too. In his only year in left field he had +6 fielding runs despite never having played the position. Then, in the next decade at second base, he averaged another +6 fielding runs every year, and didn’t have a single season when his total was below average. He led all second basemen in putouts and assists three times each, and led in fielding runs and double plays twice. Five times he had the best range in the league, and six times he led in fielding percentage. He never won a Gold Glove because he was 34 and slipping a bit by the time the award was invented, but it’s fair to say he’d have collected a few in his prime years.

Throughout his early years he could also be counted on to fill in capably pretty much anywhere on the field, and was also a .304 hitter when called upon to pinch-hit. There weren’t many things Schoendienst was excellent at on a baseball field, but he also wasn’t bad at anything.

In the middle of the 1956 season, as the team floundered around the .500 mark, the Cardinals shipped Schoendienst to the Giants. It was reported that newspaper switchboards were swamped with calls from unhappy fans, and Stan Musial, Schoendiesnt’s best friend on the team, refused to comment for one of the rare times in his career. The deal was supposedly made because younger players were blocked by him, but it didn’t do much good. A year later the GM who traded him, Frank Lane, resigned under pressure, and the Cardinals didn’t win another pennant until 1964.

By then Schoendienst was back with the club as a coach, having won another World Series with the Braves in 1957. He’d re-signed with the Cardinals in 1961, and with the exception of two years with the A’s in the 1970s, he never again worked for anyone else. He had three different stints as the team’s manager, winning over 1,000 games and a World Series, and served as a coach n both the majors and minor leagues until his death in 2018.

That’s most of 76 years dedicated to the Cardinals, and I doubt we’ll ever see anything like it again.

Tuesday

Fred Lynn turned 74 on Tuesday, and I’ll always regret that the Red Sox traded him away after a contract snafu before the 1981 season. I think he regrets it, too.

Nearly two years ago I decided to project what his career numbers would have looked like if he’d never left Fenway as his home park. He absolutely loved hitting there, sporting a career batting line of .347/.420/.601 in that park. In Fenway Park, Fred Lynn was essentially Turkey Stearnes (career .348/.417/.616 batting line), which is an enormous compliment.

What I found in that analysis was that Lynn wouldn’t have been helped as much as you’d imagine. His batting average would jump 15 points, and his slugging percentage nearly 25, and he’d have hit a lot more doubles, but his homers likely would have dropped and the rest of his numbers wouldn’t have been impacted that much. That’s because the driving factor in Lynn’s downfall as a Hall of Fame-caliber player wasn’t his removal from Fenway. It was his inability to stay on the field.

After being traded away, Lynn played just two more seasons of at least 130 games; 1982 with 138 and 1984 with 142. For his final nine years in the big leagues he averaged just 118 games per season. That’s almost 45 missed games per year, over a quarter of the schedule. It’s hard to rack up Hall of Fame numbers missing that many games.

For fun, let’s see what would have happened if he’d played 20 more games per year after leaving Boston. That’s ten seasons once we add the strike-shortened 1981 year, so it’s an extra 200 career games. This time I won’t put him back in Fenway Park, I’ll just project out his actual numbers each of those years. Doing that gives him these career totals:

I mean, okay. That’s a bit better, I guess. He’d be around 53 WAR and would have an extra 30 homers and 100 RBI and 175 hits. That’s all really good, but it still puts him in essentially the same place as Ellis Burks, another former Boston center fielder who had one park he loved to hit in (Coors Field in his case) but capped out around 2,000 games and 2,100 hits, and 340-350 homers, and 1,200 RBI or so, and got even less support for the Hall of Fame than Lynn received.

We could take some extra time and project Lynn’s numbers if he’d played more games AND stayed in Fenway, but having already given him the courtesy of a pair of “what if” projections, I don’t much see the point in combining them.

Fred Lynn was a wonderful player, and was one of the heroes of my childhood. He’s got a borderline Hall of Fame case as it is, and seems like a good guy and wonderful ambassador for the Red Sox, where he remains a very active presence. But even the most fortunate of alternative circumstances likely would have still seen him fall short of having a no-doubt Hall of Fame career.

Wednesday

This was the day Greg Luzinski retired in 1985 after pretty solid 15-year career. At one point I mercilessly mocked his defensive skills in a First Gloves entry, because someone mentioned they once had a Greg Luzinski infielder’s glove, which is the height of comedy for all who remember what Luzinski looked like on the field. Let’s just say there aren’t many infield types with the nickname “The Bull.”

But I didn’t really talk all that much about his hitting in that piece, and that was his entire reason for being in the big leagues as long as he was.

The thing to remember about Luzinski was that he was a hitting prodigy. Despite being really young for his class, he was a first-round pick of the Phillies in 1968, and immediately batted .259/.329/.467 in Low-A. In the famed “Year of the Pitcher,” that was pretty good. It’s even better once you consider he was just 17 years old. Low-A isn’t the toughest place in the world to hit, but it wasn’t easy under those circumstances. And yet, despite being over three years younger than the average player in the Northern League, Luzinksi blasted 13 homers in only 57 games.

This obviously got him promoted the next year, to Raleigh-Durham of the Carolina League, where he mashed 31 homers and drove in 92 runs despite being four years younger than the average player in that league. Both of those figures led the league. For reference, César Cedeño was also 18 years old in that league that season. He had 5 homers and 39 RBI, and a .720 OPS compared to Luzinski’s .920. Toby Harrah was also in that league, and was two years older than Luzinski, but could only manage an OPS of .838. Both Cedeño and Harrah went on to make four major league All-Star teams.

Then came Double-A Reading in 1970. All he did there was come within one homer and one point of batting average of winning the league’s Triple Crown as a 19-year old. That got him called up to the Phillies in September, and a promotion to Triple-A in 1971. He didn’t nearly win their Triple Crown, but he did hit 36 homers (third in the league), drove in 114 (fourth in the league), and batted .312 (ninth in the league among hitters with at least 500 plate appearances), and got another September call up. That audition was pretty impressive, as he hit .300/.386/.470 in 115 big league plate appearances, good enough to convince the Phillies that Luzinski was a key piece to their future. He never played another minor league game.

At 21 years old in 1972, Luzinksi was the regular left fielder in Philadelphia most of the year and had a 120 OPS+. With the exception of an injury-marred 1974 season, his rookie numbers would be his worst for the Phillies for the next 7 years. Even with 1974 included, Luzinski’s average season from 1973 to 1978 included 28 homers, 99 RBI, an OPS+ of 141, and a batting line of .291/.374/.512. Three times he hit more than 30 homers and had 29 another year. Three times he had 100 RBI, including a league-leading 120 in 1975, and had 97 and 95 in two other years. Like Cedeño and Harrah, his former competitors in the Carolina League, he made four All-Star teams. For four straight seasons he finished in the league’s top-10 in MVP voting, including a second-place finish in 1975 and another one in 1977.

Things started to slip in 1979. Though he was still only 28, Luzinski’s condition wasn’t the best. He still hit 18 homers and drove in 81 runs,, but his OPS+ dropped to 107, and now his defense, never any good, became a real liability. After batting .228 in just 106 games in 1980, the Phillies sold him to the White Sox for cash, assuming that his career, at least in the National League where he had to play in the field, was over.

They were right. With the exception of a couple of games at first base in 1983, Luzinski never played in the field again. But he could still hit. Even when hurt in his final two seasons in Philadelphia he’d managed above-average OPS+ marks, so slotting him into the designated hitter role in Chicago was the obvious move. The position was essentially invented with players of Luzinski’s type in mind.

For the next three years he thrived in the role. His 162-game averages from 1981 to 1983 included a .272/.369/.475 batting line, 133 OPS+, 28 homers, and 103 RBI. He also walked 86 times and would happily take a base after being hit by a pitch, a category in which he led the league three times in his career.

His bat speed and conditioning finally failed him in 1984 when he batted .238/.329/.364. He was still just 33 years old when the season ended, but decided to retire rather than take a part-time role with several clubs that inquired. Despite getting to the big leagues as a teenager and having a full-time job at 21, he was done at just 33.

But man, for about a dozen years, “The Bull” was no bull.

Thursday

Thursday was Henry Aaron’s 92nd birthday, which is always a good time to pass along some crazy facts about his career. For instance:

His average season in his twenties was 34 homers, 112 RBI, a batting line of .320/.375/.572, and an OPS+ of 158. He did that in 1,511 games.

In the history of baseball, only six players have played at least 1,500 games and had a career batting line of at least .320/.375/.570. All six of them (Ruth, Hornsby, Williams, Gehrig, Foxx, and DiMaggio) are in the Hall of Fame.

His average season in his thirties was 37 homers, 101 RBI, a batting line of .301/.382/.566, and an OPS+ of 161. He did that in 1,453 games.

In the history of baseball, only nine players have played at least 1,400 games and had a career batting line of at least .300/.380/.560. Eight of them are in the Hall of Fame, and the one who isn’t is Manny Ramirez.

This means that Henry Aaron’s twenties, by themselves, were a Hall of Fame career, and his thirties, also by themselves, were also a Hall of Fame career. He did both of them, back-to-back. Then he played three seasons in his forties in which he averaged 20 homers and 80 RBI per 162 games with a 107 OPS+. Unreal. Unmatched.

Friday

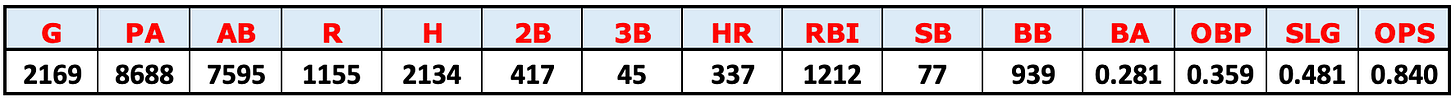

Finally, dummy that I am, I spent the first 50+ years of my life completely unaware that Henry Aaron and the man he chased for the all-time home run title, Babe Ruth, were born just one day apart. Well, 39 years and one day, but you know what I mean. So, to honor The Babe on his birthday, we’ll give him the same treatment we gave Hammerin’ Hank and review some of his more ridiculous accomplishments:

Only three pitchers since 1900 won more ballgames than Babe Ruth’s total of 67 through his age-22 season. Those three pitchers were Bob Feller (107!!), Smoky Joe Wood (81), and Dwight Gooden (73).

Immediately behind him on that list are three Hall of Famers: Christy Mathewson (64), Bert Blyleven (63), and Charles Bender (60). Walter Johnson is close with 57.

Ruth did that in three full seasons plus a handful of games when he was 19 years old. In his next three full seasons, he converted to mostly being an outfielder and averaged 41 homers and 136 RBI per 162-games, with a batting line of .336/.475/.703. He led the league in homers and slugging percentage all three years.

Can anyone imagine a world in which, for instance, Dwight Gooden decided to stop pitching after the Mets won the World Series in 1986 and immediately became the greatest home run hitter of all time? Just a mind-blowing level of talent.

This Week’s Editions

Monday: Archives: Trading Dennis Eckersley

Tuesday: Archives: What Makes an MVP?

Wednesday: Archives: Baseball Remembers Toby Harrah

Thursday: Archives: Baseball Remembers Ted Strong