Monday

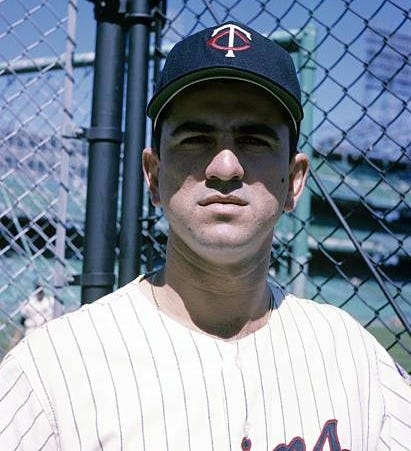

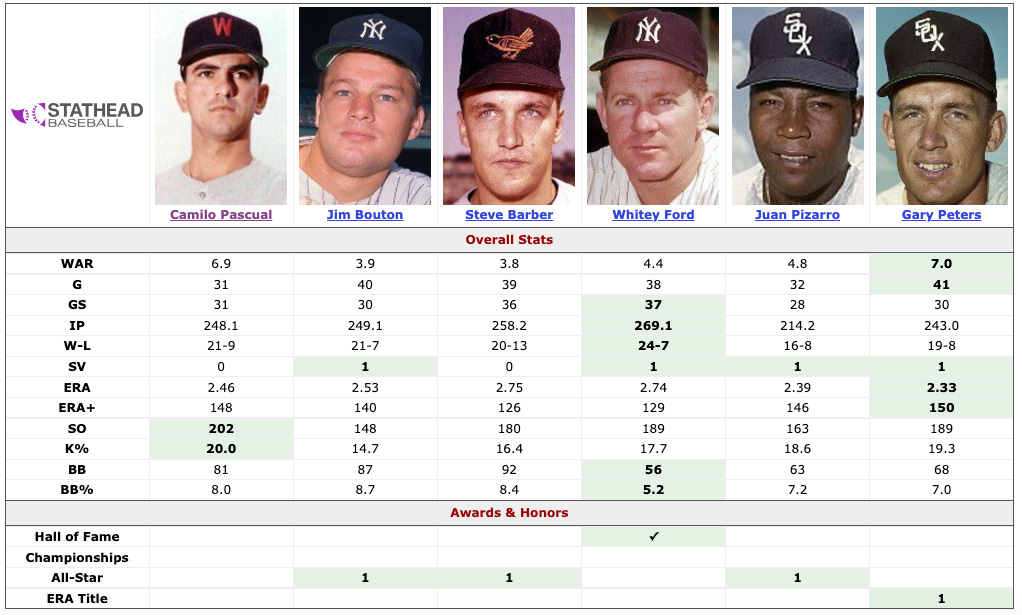

Believe it or not, but there’s a pretty good case to be made that Camilo Pascual, who born on this date in 1934, was the best pitcher in the American League for about five years. Starting in 1959, Pascual went 85-54 with a 2.99 ERA over the next 5 seasons. He led the league in strikeouts, complete games, and shutouts three times each, twice won 20 games and led in WAR for pitchers, and went to six All-Star games in those seasons when two were played most years. Compare his 1959 season to that of Early Wynn, who received the only Cy Young Award given that season.

Pascual: 17-10, 2.64 ERA, 238.2 IP, 185 K, 6 shutouts, 149 ERA+, 7.8 WAR

Wynn: 22-10, 3.17 ERA, 255.2 IP, 179 K, 5 shutouts, 120 ERA+, 2.8 WAR

Other than the win total, Pascual was better in every way, and that stat is easily explained by the fact the Wynn pitched the pennant-winning White Sox and got 5.34 runs of support each game while Pascual pitched for the last-place Senators and got 4.83 runs of support. Neutralize their stats for the context of that season and Pascual is 18-10 with a 2.60 ERA while Wynn is 16-14 with a 3.34 ERA. In other words, reproduce these numbers in 2025 when voters know enough to consider context and Pascual is almost certainly the Cy Young winner that year.

From 1959 to 1963, no pitcher in the American League had more WAR than the 27.5 compiled by Pascual, and no one was particularly close, either. Jim Bunning’s 20.5 was second, followed by Whitey Ford at 17.7. That’s two Hall of Famers trailing Pascual in this span. Speaking of Ford, it’s possible Pascual was better than him in his 1961 Cy Young-winning season, too.

Pascual: 15-16, 3.46 ERA, 252.1 IP, 221 K, 8 shutouts, 122 ERA+, 5.3 WAR

Ford: 25-4, 3.21 ERA, 283.0 IP, 209 K, 3 shutouts, 115 ERA+, 3.7 WAR

Once again Pascual was pitching for a bad team (the Twins finished 70-90-1, in 7th place) while Ford was pitching for the pennant winners. In a neutral environment Pascual would have been 16-12 with a 3.29 ERA while Ford would have been 18-13 with a 3.15 ERA. Not much difference between them.

It’s possible he was the league’s best pitcher in 1963 as well. Here are the leading candidates:

Ford’s win total probably would have carried too much weight with the voters that year, but otherwise it would have been a race between Pascual and Gary Peters for the fictitious American League Cy Young Award if one had been given. Unfortunately, these were the years when only one award was given across both leagues, and no one was taking it from Sandy Koufax that season.

None of this is meant to imply that Pascual deserves a spot in Cooperstown’s or anything. It’s just nice to recall, on his 91st birthday, that for half a decade he was the best the American League had to offer.

Tuesday

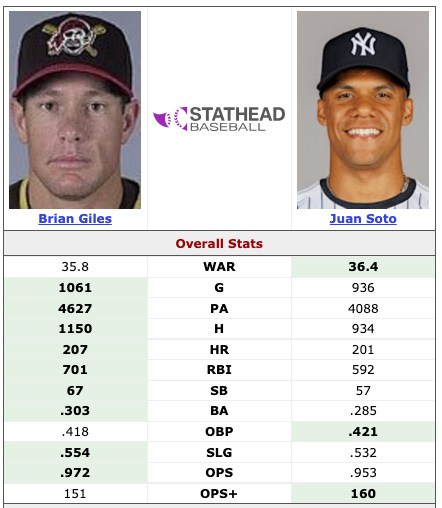

Brian Giles also had a birthday this week when he turned 54 on Tuesday. Largely forgotten now (and maybe rightfully so given some ugly domestic violence incidents and allegations of steroid use), his birthday prompted a few folks to recall him and compare him favorably to Juan Soto. Which, yeah, I guess if you squint enough you can sort of see it:

Giles undoubtedly had a fabulous peak, and it’s sort of in the same neighborhood as Soto.

But…

Note that it took him 125 more games and over 500 extra plate appearances to reach these totals, and he still fell short in WAR. That moves him a bit outside the same neighborhood. More like the same zip code.

Then consider the bottom part of that graphic that I cut off:

So, yeah, Soto did this while winning a title, playing for another, and collecting a lot more hardware than Giles. Not shown are his five top-10 MVP finishes in his seven seasons, while Giles’ best finish was a single 9th-place finish in 2005. Also not shown are the three times Soto led the league in walks (compared to one for Giles), and the time he led in runs, or slugging, or OPS, or OPS+, or WAR, or the two times he led in intentional walks or on-base percentage, all things Giles never did a single time. Soto also batted a collective .927 OPS in the postseason in these years while Giles made just one appearance and had an OPS of .516. All of which means he has to be moved out of Soto’s zip code. He can stay in the same city, I guess, but it’s way on the other side of town.

Finally, we haven’t shown perhaps the most obvious difference between them. Here’s the same comparison of the two, only it’s through age 25.

Credit where it’s due, Giles had better rate numbers than Soto at that age. Granted, it was in just 152 plate appearances, a figure Soto more than tripled when he was still a teenager, but fair is fair. That first graphic, the one floating around the internet, started in 1999 for Giles. He played that entire season at the age of 28, an age Soto won’t reach until the 2026 season is over. Having a 151 OPS+ between the ages of 28 and 34 is impressive, and Giles should get credit for that, but it’s been done by nearly four dozen players. Jack Clark did it. So did Carlos Delgado, and Frank Howard, and a roided up Jason Giambi.

But having an OPS+ of 160 in over 4,000 plate appearances before your 26th birthday is almost unheard of. You know how many people have done that?

Four.

Ty Cobb (180 OPS+ in 4,355 PAs)

Mickey Mantle (174 OPS+ in 4,116 PAs)

Mike Trout (172 OPS+ in 4,065 PAs)

Juan Soto (160 OPS+ in 4,088 PAs)

Once that’s taken into account, I don’t think we can say Brian Giles is in Juan Soto’s neighborhood, or zip code, or even the same city. It’s more like he lives on a farm in upstate New York, wearing bib overalls and picking apples near the Finger Lakes, while Soto is living in a Manhattan penthouse, trying on outfits a designer has brought him to consider wearing to the Met Gala. Sure, they’re both in New York, but it’s hard to see one place from the other.

Wednesday

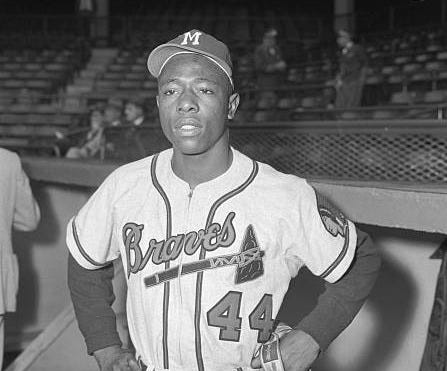

On the fourth anniversary of Henry Aaron’s passing, it’s appropriate to throw out yet another preposterous set of facts about his career.

If the active home run leader, Giancarlo Stanton, wants to reach Aaron’s total of 755, he will have to play to the same age as Aaron when he retired (42) and average nearly 41 homers in those years. Stanton has homered 41 times in a single season exactly once in his 15-year career.

If the active RBI leader, Freddie Freeman, wants to reach Aaron’s total of 2,297, he will have to play to the same age as Aaron when he retired and average over 133 RBI in those years. Freeman has never reached 133 RBI in a single season of his 15-year career.

Freeman is also the active leader in hits with 2,267. If he wants to reach Aaron career total of 3,771, he will have to average 188 hits per year until he’s 42. He’s only done that 3 times in 15 seasons.

Freeman is also the active leader in runs scored with 1,298. To catch Aaron’s total of 2,174, he’ll have to score almost 110 runs per year until he’s 42. He’s reached that mark 4 times in 15 seasons.

Andrew McCutchen is the active leader in games played with 2,127. All he has to do is play every game for each of the next 7 years, then the first 37 games of the 2032 season. In case you’re wondering, McCutchen will turn 46 in 2032.

Freeman* leads all active players with 3,866 total bases in his career. The most he’s ever had in a single season is 361. If he matches that total for each of the next 8 years, until he’s the same age Aaron was when he retired, he will still fall 102 bases short of Aaron’s all-time record of 6,856.

(*Note to self: Maybe it’s time to start thinking about where Freddie Freeman is going to rank among first basemen all-time, because he’s pretty obviously going to be in the Hall of Fame.)

Finally, Aaron is one of 17 players to reach 3,000 hits and have more walks than strikeouts. Only five of them - Aaron, Stan Musial, Rafael Palmeiro, Ty Cobb, and Tris Speaker - also had slugging percentages above .500, because guys who slug that much usually strike out a lot. Do you know who has the most hits among active players who slug more than .500 and walk more than they strike out? You’ve probably already guess that it’s the aforementioned Juan Soto, with 934 hits. Do you know who’s second? It’s a two-way tie with TWO career hits. Gregory Soto and Trent Thornton are next in line. Both of them are pitchers. There is no active position player besides Soto who qualifies. Now all he has to do is collect 2,837 more hits and keep those ratios up to match Aaron.

I will not be placing bets on any of these guys pulling off any of these feats. Henry Aaron was one of one.

Thursday

Thursday marked the anniversary of Lyman Bostock’s death in 2005. I’m not talking about the Lyman Bostock who played for the Twins and Angels in the late 70s and tragically was gunned down when he was just 27 years old. I’m talking about his dad, Lyman Sr., who lived to a ripe old age but still had his career cut short by circumstances outside of baseball.

We don’t have a ton data for Bostock’s first three seasons in the big leagues because he played for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro Leagues and they simply didn’t record a lot of stats. From 1940 to 1942 we only know of 57 games Bostock played, and that’s largely because of missing box scores. We know, for instance, that Birmingham played at least 47 league games that year, but we only have box scores for 29. The following year was similar. They played at least 45 league games, but no one on the roster is credited with more than 26. Bostock gets credit for 23 that year, but likely played far more.

What we know from that 57-game sample is that Bostock was really good. He was 22 when he joined the Barons, and in those three seasons he hit a combined .342/.386/.434, with a 146 OPS+. He wasn’t a power hitter, and in fact never hit a recorded big league homer, but he averaged 190 hits, 28 doubles, 11 triples, and 80 RBI per 162 games based on that sample, and won the Negro American League’s batting title in 1941 while making the East-West All-Star Game.

He was off to a good start in 1942, batting .308/.400/.462 in the first 8 recorded games of the season, when he was drafted into the Army for service during World War II. He missed the rest of that season, and all of the following three years as well. When he returned he was already 28, and though he had a couple more solid years (.387 in 1946; .333 in 1947), he wasn’t in true baseball shape anymore, and never latched on with a big league club once integration happened. He played a bit in the integrated Manitoba-Dakota, or ManDak, League in the early 1950s, but there’s little record of how he did there beyond the obvious fact that no major league team ever signed him.

It’s hard to find anyone to compare him to, except, ironically, his own son. These were their respective career batting lines:

Lyman Sr. - .326/.373/.406, 126 OPS+

Lyman Jr. - .311/.365/.427, 123 OPS+

It’s tragic that we weren’t able to see either father or son play a full career, uninterrupted by prejudice, war, or murder.

Friday

Finally, today is the anniversary of Warren Spahn being elected to the Hall of Fame in 1973. Since he was Henry Aaron’s teammate for so many years with the Braves, and has similarly ridiculous career totals, let’s do a similar exercise to the one above for Aaron.

If the active wins leader, Justin Verlander, wants to reach Spahn’s total of 363 carer wins, he will have to play to the same age as Spahn when he retired (44) and average nearly 34 wins in those years. Obviously, he has never won 34 games in one season. His best is 24, which he would have to match each of the next 4 seasons, then return at the age of 46 and win 5 more.

Verlander is also the active leader in innings pitched, with a 3,415.2. Presuming he pitches those five years he needs to catch Spahn in wins, he would have to pitch nearly 366 innings in each of them to match Spahn’s career total of 5,243.2. No pitcher has reached 366 innings in a single season since Wilbur Wood in 1972.

Verlander’s 26 career complete games is 356 less than Spahn’s career total. I’m not bothering to even do the math on that one.

Clayton’s Kershaw has the most shutouts among active pitchers with 15. That’s 48 less than Spahn’s total of 63. I’m not doing the math on that one, either.

Verlander, from sheer stubbornness, might actually get to Spahn’s total of 665 career starts. He’s at 526, so if he just hangs around for 4+ years and takes a turn every fifth day, he’ll get there. I don’t see that happening, but it’s not completely impossible. What is probably impossible is anyone under the age of 30 ever coming close to Spahn’s total. Lucas Giolito has the most starts of all active pitchers aged 29 and younger. He’s got 179. Does anyone see Giolito making 486 more starts? That’s nearly 15 years of taking the ball every fifth day (33 starts) without missing a turn. He’s only reached that number once in his career, and then then he promptly missed the entire season that followed. Next on the list is Germán Marquez with 174, and he’s barely pitched since 2022. Pablo López is next at 158 through the age of 28. He’s made 32 starts each of the last three years. He’d have to do that every years for the next 16 years to tie Spahn.

I don’t know what they were putting in the water in Milwaukee in the 1950s and early 60s, but whatever it was, Aaron and Spahn clearly benefitted from it.

This Week’s Editions

Monday: Time Off for Waylon

Tuesday: Educating Twitter: Lindor the Legend

Wednesday: Forgotten Treasures: Chuck Carr

Thursday: Losing the Hall of Fame’s Plot

I agree the Spahn picture is awesome. And the Giles/Soto comp is a great reminder that while numbers don't lie, they also don't necessarily tell the whole story and can certainly be manipulated to support a shaky position if you cherry-pick them.