Monday

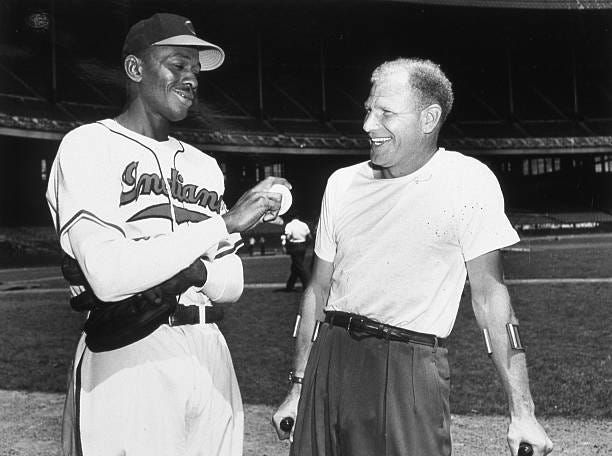

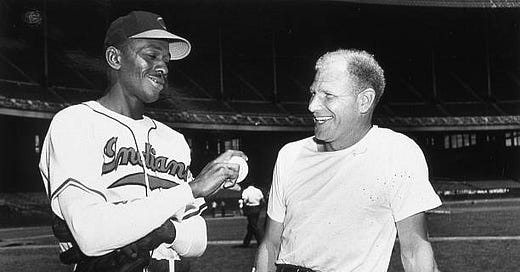

On this date in 1948, Satchel Paige signed with the Cleveland Indians on his 42nd birthday. It was a move that was greeted with particular venom from many members of the media. In particular, J.G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News mocked the signing, something he didn’t do when any number of older White players who were signed by teams that same season. Here’s an excerpt from my book with a bit more detail:

A year later, when Veeck signed 40-something Satchel Paige, Spink opened one of his ink barrels at the Bible of Baseball and condemned the move as nothing more than a publicity stunt. With a nod toward the changing times that he was about to rail against, Spink laid out a disclaimer about the motivations of The Sporting News in the criticism he was about to level at Veeck. First he made it clear that it would be unfair for anyone to oppose another person’s path to success in life solely because of their race, and that any criticism of the signing of Paige that might appear in The Sporting News had nothing to do with Paige being Black. In fact, he claimed that “no man at all familiar with the editorial policy of The Sporting News, and its reaction to the strivings of the Negro to gain a place in the major leagues, will question the motives of this paper.”

Spink then spent a paragraph giving a selective partial history of the actions of The Sporting News and its publishers, meaning himself, about furthering the cause of Black baseball players. It was classic cherry-picking, in addition to clearly being a preamble to the word “But.” He was too good a writer to use that conjunction, but that didn’t stop him from launching into his expected screed against Veeck. “The Sporting News [again, meaning Spink himself] believes that Veeck has gone too far in his quest for publicity, and that he has done his league’s position absolutely no good insofar as public reaction is concerned.” He noted that reports about Paige’s age varied from 39 to as old as 50, and that signing a 50-year-old White player wouldn’t have served the purpose of enhanced publicity that Veeck was apparently trying to achieve. Spink noted that a “rookie” of Paige’s advanced years reflected poorly on the Major Leagues overall, as it would “demean the standards of baseball in the big circuits. Further complicating the situation is the suspicion that if Satchel were white, he would not have drawn a second thought from Veeck.”

Spink finishes his complaint with an appeal to American League president William Harridge to refuse to approve Paige’s contract.

Paige was actually 42-years old, not 39 or 50. Nine other pitchers played that season at the age of 39 or older. Rip Sewell, just a year younger than Paige, won 13 games for an all–White Pirates team that was only five-and-a-half games out of first place at the time Spink wrote his complaint about Veeck and Paige. Dutch Leonard spent the entire season in the rotation of the unintegrated Phillies and led the league in losses. Spink didn’t bother to write anything about the Pirates’ or Phillies’ decisions to keep these older players in their pitching rotations. When the still-segregated Red Sox, who would finish the regular season in a tie for first place with Veeck’s Indians, only to lose a one-game playoff, signed 43-year-old Earl Caldwell two weeks after Paige signed, Spink wrote nothing. The only mention made in The Sporting News about the transaction was, “The Sox admitted pitching inadequacy when they bought ancient Earl Caldwell of the White Sox.” There was no opining about demeaning the standards of baseball, or of Caldwell’s contract being disapproved by the league office.

Paige then proceeded to prove Spink wrong. He pitched magnificently for the Indians, posting a 6-1 record and 2.48 ERA in over 70 innings of work. He worked mostly out of the bullpen but also got seven starts in the heart of the pennant race and threw a pair of shutouts. The Indians won that pennant, and the World Series, and Paige became the first Black pitcher in World Series history.

For those of you who have read the book (And for those who haven’t, what are you waiting for?), I hope you noted that I tried to be fair with the various parties who were involved in keeping Black players out of baseball and out of the Hall of Fame. True, I didn’t have many good things to write about Ford Frick, but even in his case I noted a couple of actions he took while he was serving as baseball commissioner or president of the National League that made it clear he was a bit more complex and not just a straight-up villain.

But J.G. Taylor Spink was a straight-up villain on this subject. Just an overt racist and rotten person. The day the Baseball Writers Association of America removed his named from their Career Excellence Award is one of the finest moments in that organization’s history.

Tuesday

Sometimes players end their careers in a blaze of glory. The most famous case, of course, was Ted Williams hitting a home run in his final plate appearance*, but others have had similarly satisfying final moments. Joe Mauer hit a line drive double in front of the home fans, and Derek Jeter hit an RBI infield single against his old rival, the Red Sox. The last thing George Brett ever did on a baseball field was hit a single to center field and then score on a home run.

(*Note: It’s rarely mentioned that the Red Sox had three more games on their schedule that year, a weekend series against the Yankees who had already clinched the pennant, but Williams didn’t want to make that trip and play the final games of his career in New York. I can’t say I blame him.)

Other players go out with no heroics at all, like Brooks Robinson being inserted as a pinch-hitter only to be immediately be lifted for Tony Muser when the opponent changed pitchers. He never actually came to bat in the final official game of his career.

And then there are the guys whose careers ended on pretty much the most sour note imaginable. Such was the case with Tommy Lasorda, whose final major league appearance as a pitcher took place sixty-eight years ago Tuesday. He was pitching for the Kansas City A’s by then, his long association with the Dodgers, as a player anyway, having come to an end earlier that year. He’d never managed to do much for Brooklyn at the big league level, and didn’t have any more luck in Kansas City.

Coming into that game, Lasorda had appeared in 17 games for the A’s, five of them starts, and had a record of 0-4 with a 5.20 ERA. Opponents weren’t really hitting him hard; they had a collective batting average of .229 and a slugging percentage of .361. The problem was that he seemed to be allergic to the strike zone. Opposing hitters had a .390 on-base percentage against him because Lasorda had walked 42 batters in just 45 innings of work. He’d also hit three batters and thrown seven wild pitches. He was pretty much a mess.

On this day, the Indians had a 4-2 lead heading into the top of the seventh inning. A’s starter Jack McMahan gave up a leadoff single, then got an out on a sacrifice bunt, then surrendered an RBI double to make the score 5-2 Cleveland. Manager Lou Boudreau had seen enough and called upon Lasorda to relieve. This is what his final outing as a major league pitcher looked like:

Walked Al Rosen

RBI single by Sam Mele

Groundball force out at second by Jim Busby

RBI single by Chico Carrasquel

Walked Jim Hegan

Walked pitcher Early Wynn to force in a run.

At that point Boudreau pulled Lasorda. He never pitched in the majors again, but continued to surrender runs because reliever Jack Crimian walked in Carrasquel, allowed Hegan to score on a single, and allowed Wynn to score on a double.

So, officially, Lasorda’s line for the game was 0.1 inning pitched, faced 6 batters, surrendered 2 hits, 3 walks, and 5 earned runs. The last thing he did as a major league player was issue a bases loaded walk to a pitcher.

It’s a good thing he turned into a Hall of Fame manager, because his actual playing career was sort of a train wreck, particularly the ending.

Wednesday

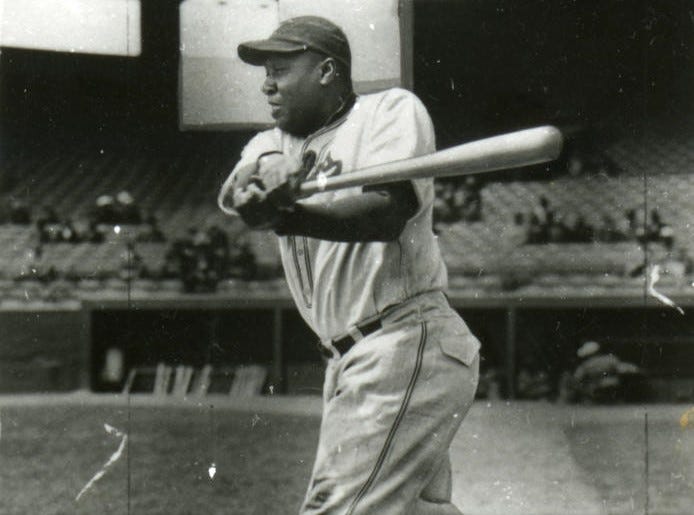

Folks, let’s talk a bit about how dominant Mule Suttles was. Wednesday was the anniversary of his death in 1966, which means he passed away before getting the opportunity to enjoy his induction into the Hall of Fame, which wouldn’t take place for another forty years. In fact, he died before getting to see anyone enter the Hall of Fame for their time in the Negro Leagues. That’s a damn shame, because no one embodied the Negro Leagues or represented the dominance of some of the players in them like Mule Suttles did.

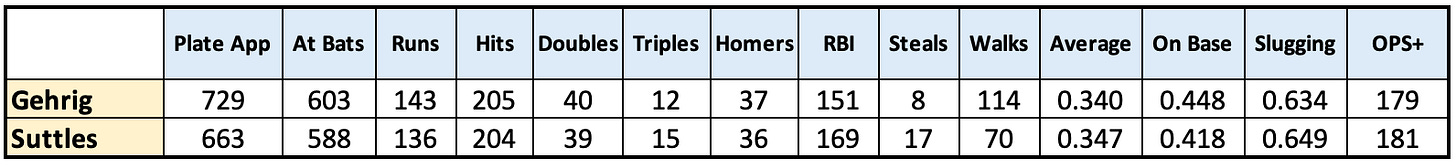

Just to give you a sense of exactly how incredible he was, I want you to picture Lou Gehrig in your mind. Do you have him? Big, solid guy with preposterous statistics from the 1920s and 1930s, right? Still often referred to as the greatest first baseman ever, yes? Here’s what Gehrig’s 162-game averages were were from 1925, his first year as a regular player, until 1938, his last one.

205 hits

143 runs

40 doubles

12 triples

37 homers

151 RBI

114 walks

.340 batting average

.448 on-base percentage

.634 slugging percentage

179 OPS+

Dominant, obviously. Now here are those averages next to Mule Suttles’ averages while playing the exact same position in the exact same years.

Pretty much the same. Unfortunately, despite being equally productive on the field, there was nothing equal about how they were treated off the field.

When Gehrig retired abruptly in 1939, he was immediately and unanimously whisked into the Hall of Fame on a special ballot, the five-year waiting period waived due to his health. Partly that was because of his illness, of course, but there’s little doubt that Gehrig would have been inducted into the Hall at the first possible moment even if he’d never been sick.

Conversely, Mule Suttles had been in his grave for five years by the time anyone from the Negro Leagues was allowed into the Hall of Fame, and for forty years by the time his own plaque was hung in the gallery.

Just in case you’re ever in a conversation with anyone about exactly how “unfair” it is to include Negro Leagues statistics in the major league record books, feel free to cite the case of Mule Suttles as an illustration of the exact nature of baseball’s unfairness regarding the Negro Leagues and those who played in them.

Thursday

This was the anniversary of Jim Wynn’s major league debut with the Houston Colt .45’s in 1963. In addition to having one of the best nicknames in baseball history, The Toy Cannon also serves as an excellent example of exactly how much a player’s home ballpark matters.

Baseball-Reference.com has a Neutralized Stats feature that allows us to see how a player’s actual numbers project to a more neutral run scoring environment. For some players their numbers barely move because they played in ballparks and seasons where run-scoring was close to the historical average. For others, like players for the Rockies in 2000, there’s a huge downward shift when we look at their neutral stats, because they had enormous advantages compared to other hitters across major league history.

And then there are players like Wynn, whose neutralized stats tell a different tale, serving as a testament to exactly how difficult it was for him to hit in the ballparks he called home for most of his career, not to mention the low run-scoring environment of the National League in general in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Wynn first played in Houston’s Colt Stadium, which suppressed run scoring by about 7% in his rookie year, while the league overall scored only 3.81 runs per game. Here’s how he actually did compared to how he might have done in a more neutral ballpark and time period.

1963

Actual: 4 homers, 27 RBI, .244/.319/.372

Neutral: 4 homers, 32 RBI, .265/.342/.401

1964

Actual: 5 homers, 18 RBI, .224/.301/.324

Neutral: 5 homers, 20 RBI, .238/.317/.341

Not a huge shift in the counting stats because he was still a part-time player, but those are pretty big shifts in his batting lines. Then the team moved to the Astrodome and changed their name to the Astros. In the ballpark’s first year it suppressed run scoring by 11% compared to the rest of the league. That was also the first year Wynn got regular plying time.

1965

Actual: 22 homers, 73 RBI, .275/.371/.470

Neutral: 24 homers, 83 RBI, .293/.391/.503

1966

Actual: 18 homers, 62 RBI, .256/.321/.440

Neutral: 19 homers, 69 RBI, .268/.335/.459

1967

Actual: 37 homers, 107 RBI, .249/.331/.495

Neutral: 40 homers, 124 RBI, .266/.351/.526

1968

Actual: 26 homers, 67 RBI, .269/.376/.474

Neutral: 30 homers, 85 RBI, .300/.412/.529

1969

Actual: 33 homers, 87 RBI, .269/.436/.507

Neutral: 34 homers, 93 RBI, .277/.447/.521

1970

Actual: 27 homers, 88 RBI, .282/.394/.493

Neutral: 27 homers, 86 RBI, .279/.391/.491

Notice that in 1970 Wynn’s neutralized stats are worse than real life for the first time. That wasn’t because the Astrodome suddenly became a pitcher’s park. With the exception of a couple of years where it fluctuated to being sort of average, the ballpark always suppressed scoring, particularly home runs. The 1970 change wasn’t due to the ballpark, it was due to the league’s overall scoring environment going up significantly, from 4.05 runs per game to 4.51. It dropped back down to 3.91 the next season, which happened to be Wynn’s first bad year as a regular.

1971

Actual: 7 homers, 45 RBI, .203/.302/.295

Neutral: 8 homers, 50 RBI, .215/.316/.315

1972

Actual: 24 homers, 90 RBI, .273/.389/.470

Neutral: 27 homers, 104 RBI, .286/.405/.492

1973

Actual: 20 homers, 55 RBI, .220/.347/.395

Neutral: 20 homers, 57 RBI, .224/.351/.398

Wynn was traded to the Dodgers before the 1974 season, exchanging one terrible hitter’s park for another. Dodger Stadium was notorious as a place baseballs went to die, and though it wasn’t quite the same in 1974 as it had been in the sixties when the mound was higher and scoring was lower, it still suppressed run scoring by 7% compared to the league.

1974

Actual: 32 homers, 108 RBI, .271/.387/.497

Neutral: 33 homers, 116 RBI, .279/.396/.510

1975

Actual: 18 homers, 58 RBI, .248/.403/.417

Neutral: 19 homers, 63 RBI, .258/.417/.435

After that Wynn’s career sort of fizzled out. Finally traded to a good hitter’s park (Atlanta), he had one decent year there in which he led the league in walks and hit 17 homers, but then divided the 1977 season between Milwaukee and the Yankees and played poorly at both stops.

Still, the overwhelming majority of his career, and all of his prime, was spent in ballparks that drastically suppressed offense. When everything is added together, here is how Jim Wynn’s actual career numbers look next to numbers from a neutral hitting environment:

Now, those revised numbers don’t make Jim Wynn a Hall of Famer. His career was still pretty short, and he wasn’t a great defender despite being left in center field most of his career, he ran well but didn’t have a good success rate stealing bases, and he wasn’t a good playoff performer. That’s not really the point, which is that something as basic as where a player plays their home games can have an enormous impact on their career numbers and on their legacy.

Would Jim Wynn have been elected to the Hall of Fame if he had those neutral numbers? No. But would a center fielder with 300 homers, 1,000 RBI, and almost 1,300 walks have received a bit more attention during and after his career? More than three All-Star appearances and zero Hall of Fame votes? Yes, he would have.

Friday

Bobby Bonilla signed his first pro contract on this date in 1981. He was an undrafted free agent, but the Pirates saw something in him and offered him a deal anyway. Now known for a different contract signed many years later that still sees him paid over a million dollars by the Mets on July 1 of each year, it’s kind of unfortunate that his career has been reduced to an annual punchline, because he was a really good player for a long time.

From 1987 through 1997, Bonilla’s average season included 24 homers, 93 RBI, and an OPS+ of 133. He made six All-Star teams in those years, drove in over 100 runs four times, led the league in doubles once, and had back-to-back years in which he finished second and third in MVP voting.

Now, he always had some limitations, especially defensively, and he struggled to make an impact in the postseason despite getting there six different times, but the guy could flat out hit. There’s a reason he earned that big contract that keeps him in the news every year. He then made a savvy business deal that turned the final $5.9 million he was owed into nearly $30 million, and gets to enjoy receiving a seven-figure check every year during his retirement while polishing his 1997 World Series ring.

Seems like a pretty solid career, doesn’t it?

This Week’s Editions

Monday: Archives: Triple Crown Winners and the Hall of Fame

Tuesday: Archives: The Weirdest MVP

Wednesday: Archives: Bob Feller and World War II

Thursday: Archives: Baseball Remembers Troy Percival

Hey, there’s a reason the Mets paid so much for Bonilla!