Archives: What Makes an MVP?

(Note: We’re on a bit of a vacation this week, so these editions will be from our archives. This one was first published two years ago, in January 2024. Here is is, edited a bit and unlocked for everyone.)

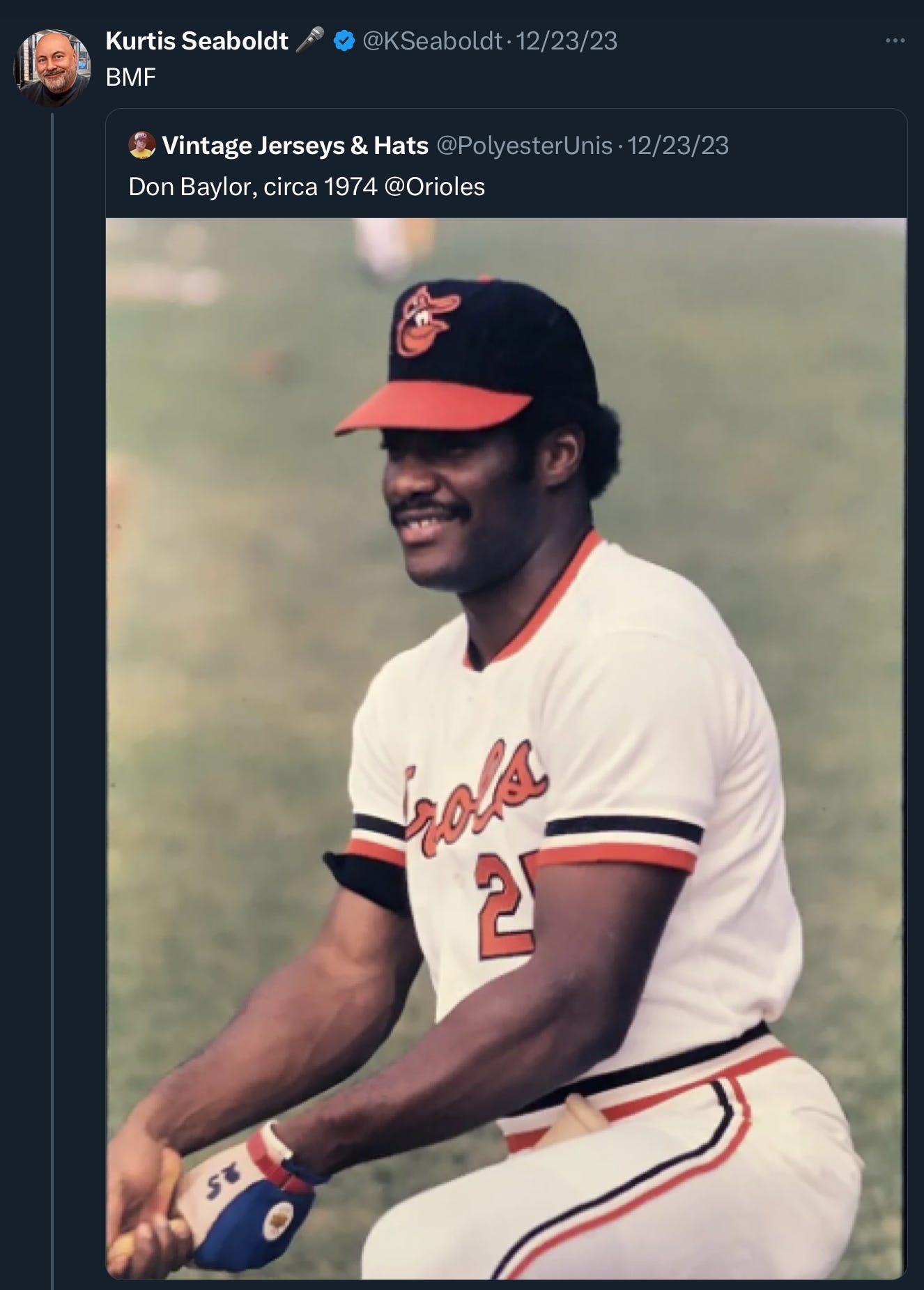

This one doesn’t really fall under the heading of “education.” It’s more like a good discussion, which is pretty rare for Twitter these days, so I thought it was worthy of being highlighted. It started this way:

I run this as family-friendly newsletter, so I won’t translate BMF for everyone. Use your best googling skills wisely folks. I will say, though, that I agreed with that assessment of Don Baylor, because he very much had the reputation of being a bad so-and-so who stared down pitchers, leaned into pitches, broke up double plays, and was a strong clubhouse voice everywhere he played. At the same time, I noted that he was pretty overrated as an actual ballplayer, especially in his MVP year, which led the original poster to make an interesting point.

If you don’t know Kurtis Seaboldt, he’s a sports radio personality and announcer here in Kansas City, and a very good one. He’s also very knowledgeable on top of being articulate, so it’s always a good discussion when he’s involved.

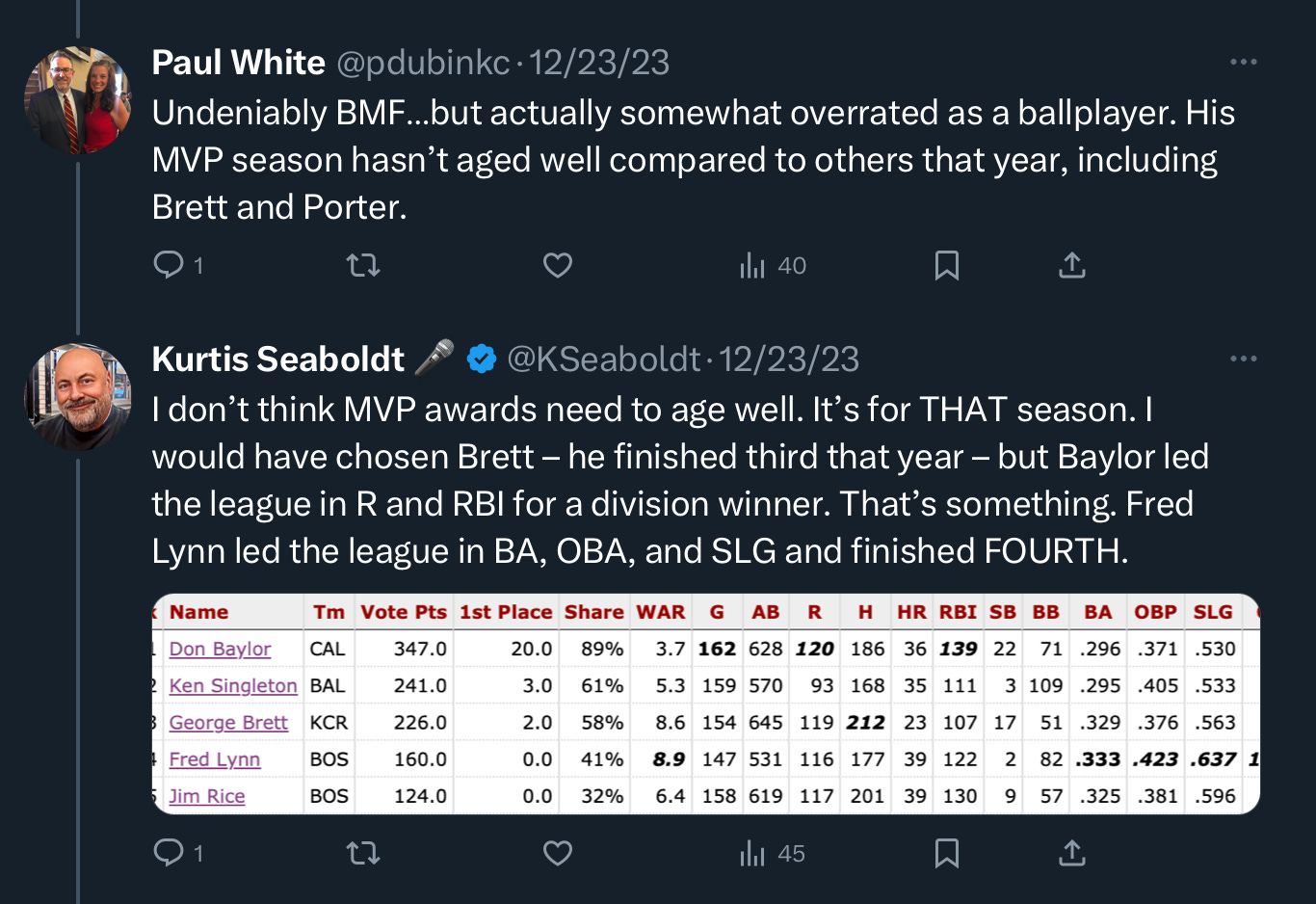

I think he brings up a good point here. Not about Baylor, per se, because I still think there were better players that season in the American League. We agreed later in the exchange that Fred Lynn probably would have won the award if they evaluated players in 1979 the way we do now.

But Kurtis’ point about MVP’s being for THAT season only, and not really needing to hold up over time, has some validity. Like it or not, the award has never strictly been viewed as the “Best Player of the Year Award.” Countless players have won the MVP when we all knew, even at the time, that they weren’t the best player in the league.

I’ve written about a couple of those instances, like the 1934 AL MVP going to Mickey Cochrane when he clearly wasn’t even the best player on his own team. His status as player-manager of the Tigers, though, was given extra weight in the “value” department and he was voted the MVP. Likewise, I suspect no one actually thought Mo Vaughn was the best player in the American League in 1995. As I wrote in that piece, it’s pretty clear that Vaughn wasn’t even the best player on the Red Sox that year, let alone in the entire league, but he was a good hitter with a strong clubhouse voice on a division winner and that mix got him the MVP.

Personally, I’m not a fan of that method of giving out the MVP. I view it as the Best Player of the Year Award, even though I know it’s not. Any leadership or motivational components of a player’s contributions to his team are valuable, no doubt, but they should probably be honored in a different way.

For instance, most members of the 2004 Red Sox will tell you that the best teammate on that roster was Gabe Kapler, a good guy who was sort of the glue of the team, even though he was the fourth outfielder and no one’s idea of the best player. Kevin Millar also gets tons of credit for being the guy who kept that team loose and motivated, doing his whole “Cowboy Up” routine, having guys drink shots and shave their heads and whatnot. Again, nowhere close to being the best player on the team or in the league, but remarkably valuable nonetheless.

Well, that was sort of Don Baylor’s niche with the Angels in 1979. He was the guy who ran the clubhouse kangaroo court, and made sure guys played the right way. He’d run hard, and slide hard, and show up every day no matter how many fastballs had bounced off his body. There’s incredible value in that, and he absolutely deserves credit for it.

But he wasn’t remotely the best player in the American League. As I said, Lynn had a much better year, but so did George Brett, and Darrell Porter, and Jim Rice, and Buddy Bell, and Willie Wilson, and Ken Singleton. I mean, look:

All but Bell had similar or better offensive numbers, but Bell was also playing Gold Glove defense at third base. All but Singleton played the field mostly, while Baylor spent nearly 70 games as a DH, and was a bad left fielder the rest of the time. And just between the two DH’s, Singleton had the better offense.

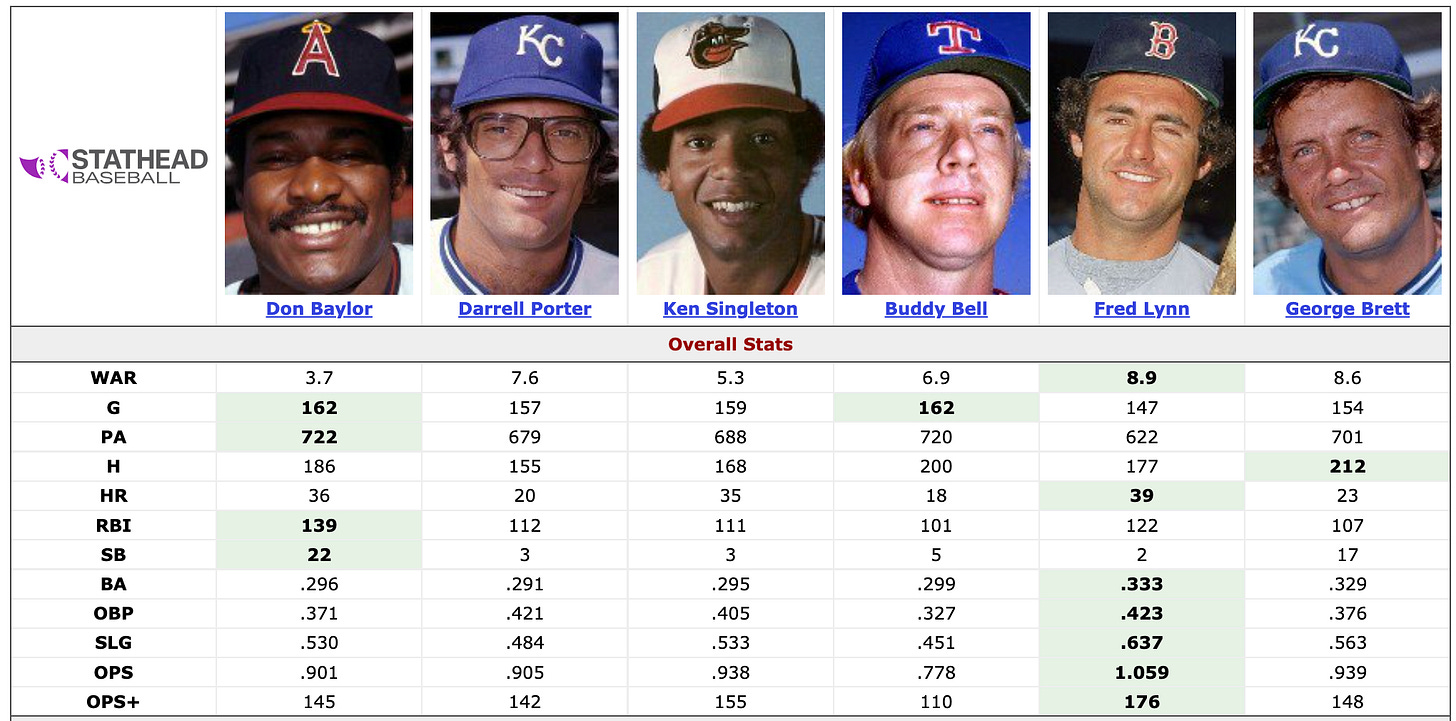

More importantly, Baylor wasn’t even the best player on the Angels. Both Bobby Grich and Brian Downing were simply better players that season.

Their offense was similar, but both Grich and Downing played defense at premier positions, while Baylor didn’t, and defense still matters. A lot. A catcher with a 142 OPS+ or a second baseman with a 145 OPS+ is simply doing more for his team than a DH/left fielder with a 145 OPS+. I don’t think that’s terribly debatable.

But that’s where Kurtis’ point comes into play. Baylor didn’t win the MVP in 1979 because he was the best player in the league, or even the best player on the California Angels. He won for the same reason Kirk Gibson was the National League MVP in 1988, or Terry Pendleton was the NL MVP in 1991. He won because he was the best good player that season who also brought other things to the table that are harder to measure.

His case was an easier one for the voters because he also happened to compile a league-leading number of RBI, and for some voters that’s probably all they needed to see. But, on top of that, he brought those elusive intangibles as well, the kind that make for good narratives in newspaper columns, and good quotes in game stories. Those narratives tend to die hard once they’re out in the world, especially since the same people spinning those narratives are the ones voting for the awards when the season ends.

All of that made Don Baylor an MVP in 1979. As Kurtis notes, that doesn’t necessarily have to age well, and might even look silly now. Personally, I think it does. But, just as “flags fly forever” when a team wins a pennant, Don Baylor’s name is always going to be etched on that MVP plaque. And while he was still living, I suspect he saw no need to apologize for it.

Excellent take on how MVP voting reflects narrative over pure performance. The Baylor example really underscores how leadership metrics get baked into these awards even when the numbers don't support it. I've seen this same dynamic in tech with "10x engineer" discussions where cultural fit and mentorship get conflated with actual ouput, making it almost imposible to evaluate contributions objectively.