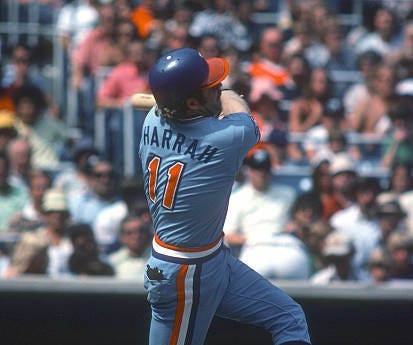

Archives: Baseball Remembers Toby Harrah

(Note: Our break continues this week, so here’s another archived edition. This one ran in September, 2023, featuring my favorite big leaguer with a palindrome for a last name, Toby Harrah. It’s been edited and unlocked for everyone.)

From Dictionary.com:

palindrome [pal-in-drohm]

noun

a word, line, verse, number, sentence, etc., reading the same backward as forward, as Madam, I’m Adam or Poor Dan is in a droop.

Biochemistry. a region of DNA in which the sequence of nucleotides is identical with an inverted sequence in the complementary strand: GAATTC is a palindrome of CTTAAG.

I don’t know anything at all about the kind of palindrome that refers to biochemistry or DNA, unless it can be condensed into a plot point in a courtroom drama. But I do know that a word or sentence that reads the same backward and forward is called a palindrome, and I’ve always found them sort of cool.

Consequently, I always thought Toby Harrah had a cool name. I absolutely loved getting his baseball cards when I was a kid. What I never appreciated at the time, though, was that beyond having cool baseball cards and a palindrome last name, Toby Harrah was also a really, really good baseball player.

Originally signed by the Phillies as an amateur free agent after the 1966 season, Harrah immediately demonstrated a very patient approach at the plate despite being only 18 years old in 1967, drawing 46 walks in just 63 games for the Phillies’ Low-A affiliate in Huron, South Dakota. Despite that, he was left unprotected in the minor league draft after the season, and was taken by the Washington Senators and assigned to their High-A team in Burlington, North Carolina. Still just 19 years old in 1968, he batted just .239 but drew 90 walks while playing decent defense at shortstop and stealing 25 bases.

That performance made him a real prospect, so in 1969 he was promoted twice by the Senators. After hitting .306/.395.442 with Burlington again, he was promoted to Double-A Savannah of the Southern League, and then got a brief eight-game call-up to the big leagues that September. The Senators changed their Double-A affiliate to Pittsfield, Massachusetts before the 1970 season, and that’s where Harrah spent the entire year working on his hitting. He improved his batting average to .276 without sacrificing any of his trademark plate discipline, and he stole 27 bases in just 33 attempts, making him a favorite to make the Senators’ lineup in 1971.

That’s exactly what he did, earning a roster spot on Opening Day and never spending another day in the minor leagues. With Ted Williams as his manager, a man who always appreciated someone who knew how to get a good pitch to hit, Harrah kept the shortstop job for most of the year. It was a struggle, as the 22-year old batted just .230/.300/.290 and hit only two home runs, but he showed the team enough to stick on the roster the whole year.

He also had the distinction of being the answer to a trivia question as the last player to ever come to bat in a Senators uniform. Harrah was at the plate when Tommy McCraw was caught stealing to end the eighth inning of their final game of the season, a home win over the Yankees. After the season, the team moved and became the Texas Rangers.

Harrah missed almost 50 games in each of the next two seasons in Texas, but his hitting progressed well anyway. He improved to .259/.316/.321 in 1972, and then to .260/.328/.364 in 1973, while stealing 26 of 36 bases and continuing to play good defense at shortstop.

In 1974, still only 25 years old, Harrah really blossomed. For the next five seasons his average year included 153 games, 636 plate appearances, 74 runs, 140 hits, 22 doubles, 19 homers, 76 RBI, 21 steals, 86 walks, 67 strikeouts, a batting line of .262/.366/.419, an OPS+ of 123, and 4.7 WAR. He made two All-Star teams in those years and led the American League with 109 walks in 1977. That was the same year Harrah shifted to third base to make way for newly-acquired shortstop Bert Campaneris.

Harrah was quite popular with the fans in Texas, and was well-liked in the clubhouse as well, having earned a reputation as a practical joker with his teammates. The team showed tremendous improvement during these years, finishing second in the AL West in 1974 and 1977, and third in 1978. But they were in the same division as the Kansas City Royals, winners of three straight division titles, and management decided they weren’t going to catch them without shaking up the roster.

Part of that shakeup involved trading Harrah to the Cleveland Indians in a straight-up exchange for third baseman Buddy Bell.

It was a terrible deal for Harrah in a couple of different ways. First, Bell was a fan favorite in Cleveland, and nothing Harrah did once he arrived there seemed to be good enough. The local beat reporters compared him unfavorably to Bell with regularity, and he became bitter about it.

The second reason was that Bell immediately played great baseball for the Rangers. Over the next six full seasons, Bell won the Gold Glove every year, made four All-Star teams, and averaged 16 homers and 90 RBI per 162 games to go along with 6.5 WAR. There wasn’t anything wrong with Harrah’s performance in Cleveland. He spent five years there, and his 162-game averages weren’t much different from what he’d done in Texas, including 16 homers, 74 RBI, a 120 OPS+ and 4.0 WAR. He remained a very good player, but he wasn’t Buddy Bell, and Cleveland fans never warmed up to him.

He was traded to the Yankees after the 1983 season, and has said that he’s glad he played there for a year to experience the tradition and pressure of New York first-hand. At the same time, it was unsatisfying for him professionally as he was platooned at third base with Roy Smalley and totaled less than 300 plate appearances.

As a result, Harrah was thrilled to be sent back to the Rangers before the 1985 season, and enjoyed one final good year. Playing second base regularly for the first time, he batted .270/.432/.389, good for a 127 OPS+. That exceptional on-base percentage trailed only Wade Boggs and George Brett in the American League, and was due to a career high of 113 walks, which missed leading the league by just one.

Harrah played one more year, but had clearly lost his ability and retired after the 1986 season. His career totals were disappointing only in that he narrowly missed some milestones that would have allowed him to receive more attention. He finished with 1,954 hits instead of 2,000, and 195 home runs instead of 200, and 918 RBI instead of 1,000. He never drove in 100 runs, or won a Gold Glove though his defense was perfectly fine at both shortstop and third base.

Most disappointing is that in parts of 17 major league seasons he never played for a playoff team. His 2,155 career games as a player with no postseason appearances is the seventh-most in MLB history, trailing four Hall of Famers (Ernie Banks, Luke Appling, Ron Santo, and Joe Torre), along with Mickey Vernon and, ironically, Buddy Bell.

Still, Toby Harrah was a really good all-around player. He had excellent plate discipline and good power, stole 238 bases including a high of 31 in one season, was very durable, could play any infield position well, and was a good guy to have in the clubhouse. That’s a pretty good career to have, and certainly one worth remembering.

Thankfully, his palindrome name should make that easy.

This article just reinforced my childhood memories of Buddy Bell and Toby Harrah being the same player somehow. On a separate note, I always find it astonishing that Pittsfield MA had a AA team. What a different world this used to be.

I am an equally fervent admirer of palindromes... and saw Toby Harrah play in the first game(s) I ever attended at a ballpark. It was Fenway Park, May 1976, and the Rangers were playing a scheduled doubleheader against my Red Sox. Texas won both, 6-5 and 12-4. He indeed had a solid career....and I was unaware of his being the last Senator at the plate ever. Bonus that it was in a victory over the dreaded Yankees. Good stuff!